Eglinton Crosstown makes infrastructure exciting again, Marianne McKenna sits on Metrolinx board

Article content

Click here to view The Globe and Mail

If a government spent billions of dollars on public buildings, would you expect them to be beautiful? Would you expect them to contribute to their streets and to the city where they sit?

Of course you would. But when enormous building projects are classed as “infrastructure,” too often the idea of design quality disappears. That shouldn’t be. The Eglinton Crosstown LRT line under construction shows how good urban design and architecture can be part of the package, the result of Metrolinx’s “Design Excellence” initiative.

Yet the $6-billion effort also reveals just how hard it is – within a government process that favours lawyering and risk mitigation – to focus on delivering high-quality places for the public.

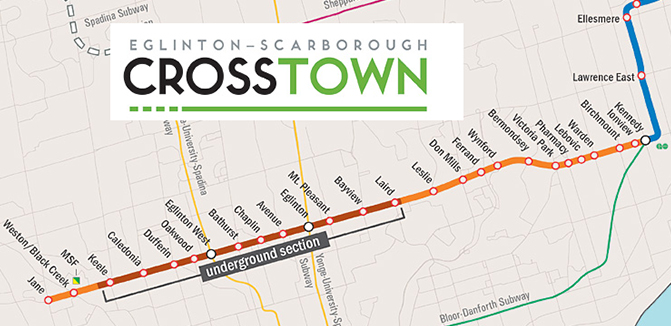

First, the stakes. The Eglinton Crosstown is the biggest single transit project in the country, with a budget of $6.63-billion. Covering 19 kilometres, about half of it below ground, it is a massive build that will remake Toronto’s midsection from Weston Road to Scarborough.

At street level, that translates into a huge footprint: The stations and stops are a portfolio of buildings that will remake blocks across the city, some of which – particularly west of Bathurst Street – really need a better public realm. At the west end, the Mount Dennis station integrates a 1940 building that was part of the Kodak manufacturing complex with a generous underground platform and a massive maintenance complex; at the east end, Kennedy station is a large above-ground white box adjoining a generous, well-designed plaza.

Across the line, the stations, which are 90 per cent designed, have a consistent vocabulary, combining glass-box entry pavilions with minimally detailed “technical boxes,” and stations organized to let in as much light as possible. The landscape includes well-detailed public plazas and, in some cases, green trackways that will vastly improve the street and help bring high-quality development.

They look excellent on paper. If built that way – and we’ll see – they will constitute a good and important set of civic spaces for Toronto.

So who designed them? First the Toronto architecture and landscape architecture firm GH3 was hired to create “demonstration designs,” as part of the Design Excellence Principles for the project.

Those designs were boiled down into a set of detailed principles. Then those principles were included in the “project-specific output specifications,” the standards and requirements to which competing builders had to commit.

The winner, Crosslinx Transit Solutions, is a consortium that includes construction firms Ellis-Don, Aecon, ACS-Dragados and the engineering giant SNC-Lavalin. It hired the architecture and design firm IBI. IBI staff, in turn, did some of the architecture and landscape architecture themselves, while architecture firms NORR, DIALOG and Daoust Lestage led the design for individual stations. “There is a kit of parts in the design,” IBI architect Charlie Hoang says, “that are consistent across the system.”

That “kit of parts” – the architectural language – was developed largely by Daoust Lestage, the small-but-much-decorated Montreal firm that did the urban design for Montreal’s Place des Festivals and Quebec City’s Promenade Samuel-de-Champlain. It served as “Design Excellence consultants” for the winning design team.

In essence, a strong and clear design vocabulary by GH3 was converted into legalese, then reverse-engineered from jargon into physical form and detailed an army of designers who are working for a construction company.

This, apparently, is a sensible way of doing business. But it certainly is not the best way to create good places. There are many cooks and the designers are way down in the hierarchy working, not for the government, but for the builders.

When I met Mr. Hoang, he spoke highly of Daoust Lestage, which has designed in collaboration with the much larger firm. “We have an excellent working relationship,” he said. “We have the engineering consultants, and the Design Excellence consultants, who we work closely with.”

Why is “quality” just another attribute of a big piece of infrastructure? And who will make sure, when the last decisions are being made about construction details and materials, that the vision will survive?

These are tough questions. The project is being delivered by Infrastructure Ontario (IO) through the alternative finance and procurement model – a version of the public-private partnerships favoured by several provincial governments and the federal government. In simple terms, these reduce the risk of cost overruns and delays by combining the building and maintenance (30 years for Crosstown) of the system in private hands.

It delivers certainty, but it doesn’t come free. Ontario Auditor-General Bonnie Lysyk reported, in 2014, that the process had added $8-billion over nine years to the cost of Ontario projects.

Yet such models are here to stay. Metrolinx, to its credit, has tried to make sure that good design remains part of these mammoth public works. Its Design Excellence program, headed until a few months ago by architect Beth Kapusta, has the right ambitions: to acknowledge that huge projects such as this can be great and that good design – well-resolved details, thoughtfully connected spaces, good finishing materials, wayfinding – is affordable.

But the emphasis of this sort of procurement process is all about cost and time. The Eglinton project will show whether such work can be good, as well as timely and on budget.

Marianne McKenna, an architect who sits on Metrolinx’s board, has been a strong advocate for that view. The agency should be “pushing ‘design thinking’ as a tool for improving the user experience across the many touch points of travel …putting the customer at the centre of everything we do,” she says. “There are many aspects to this – beyond laying down track and trains, but also focused on using the physical realm and digital communication to move people seamlessly through the region.”

The stakes are high. “Metrolinx having more control over the design component, as the client so to speak is, in my opinion, a critical part of this,” Ms. McKenna says. “Let’s have IO focused on delivering a quality product, on time, and on budget and Metrolinx focused on providing world-class design to create an integrated transit network across the region. There are so many great international precedents for integrated transportation – we should be looking at the best to create the best.”

Do we want the best? Or do we simply want the trains to run on time?

Related News

Year in review: Highlights from 2025

December 17, 2025Contemporary Calgary receives Canadian Architect Award of Merit

December 1, 2025

)

)

)